Whether you’re outside China and trying to get in, or inside China and trying to get out, a well-known barrier sits between the Chinese internal network and the wider internet. The Great Firewall of China (防火长城) acts as a giant filter between the two networks, restricting access to external sites considered unsavory by the Chinese government.

Outside of government circles, the block list is mostly unknown, with websites being added to, or removed from, the blacklist on a whim. Many of the foreign-run social networking sites suffer from being permanently blocked, causing Chinese netizens to instead turn to homegrown solutions.

With its own internet evolving in parallel to the wider internet, Chinese developers have always lived in online isolation, away from the innovation occurring in the wider world. This has lead to similar apps being created in both environments to meet resident requirements. Sometimes these apps beat the functionality of international services.

For social networking and ecommerce, Weibo and WeChat replace Twitter, Facebook, WhatsApp, and eBay; for the kinds of services provided by Lyft and Uber, the Chinese use the equivalent service Didi Chuxing. Even dating apps like Tinder have their Chinese equivalent in Tantan. Each app has functionality at least on par with its more globally used counterpart, because at the end of the day, app developers and companies are looking to meet the end user need. That’s something that typically extends globally, disregarding country borders.

Other countries have considered implementing a country-wide filter with the intention of protecting their citizens. It’s my opinion, however, that a government that restricts the availability of the internet to its residents is both against net neutrality and an invasion of privacy. The policy to deploy a ‘Great Australian Firewall’ proposed in 2008 by Stephen Conroy was shot down in 2012 and removed from consideration as it would have not only slowed Australian access to external internet sites to a crawl (hampering business) but it would be trivial to circumvent using basic Virtual Private Network (VPN) technology.

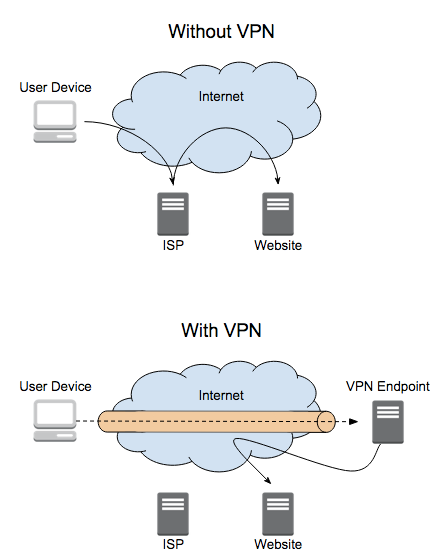

For those in China wishing to access the internet and all its functionality outside of the country, a technical solution exists. The use of VPNs and SSH tunnels is widespread and commonplace. By sending all traffic through an encrypted tunnel out of the country, domain names and their associated IP addresses are not discernable by the GFW. Instead all that is seen is a lot of scrambled network traffic to one particular external IP address.

While there have been hints of the GFW’s ability to run deep packet inspection (http://technode.com/2016/03/17/behind-scenes-heres-vpn/) on all internet traffic with the aim of uncovering and blocking VPN connections, this is fraught with the same challenges that faced the Australian government’s bid to create a Great Australian Firewall. Any VPN block will affect not only private citizens but also corporations communicating securely between offices. This simple fact, that a VPN block would lead to a loss in profitability, makes the thought of any block to VPN traffic untenable.

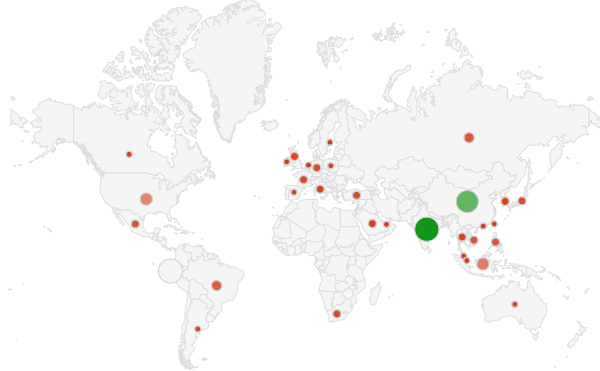

Taking data from the World Population Clock (http://data.stats.gov.cn/) and the globalwebindex’s studies on VPN usage (http://www.globalwebindex.net/blog/15-for-15-generation-v) we can see that with 25% of the Chinese population frequently using VPNs it puts them as one of the highest users by number globally.

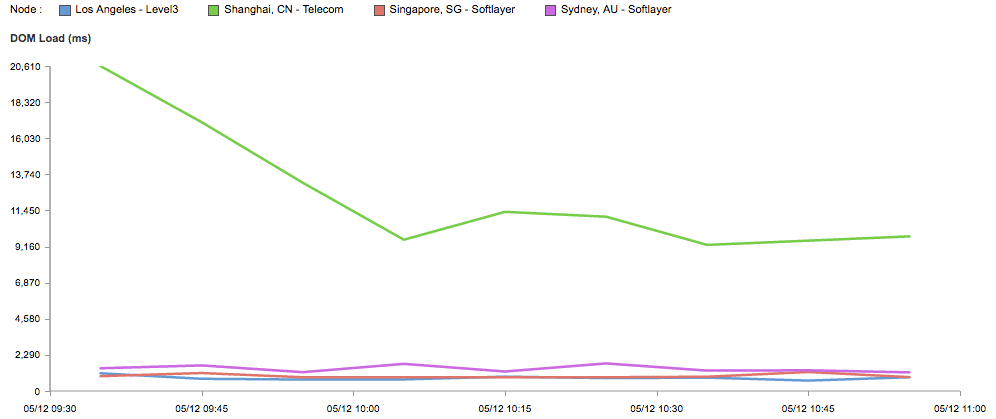

The other issue to contend with when delivering content into China, presuming your site hasn’t been blocked, is the latency added by GFW traversal. Website load times are on average 10 seconds slower when loaded from within China compared to outside. Running tests from Shanghai, Singapore, Sydney and Los Angeles against a site I run out of Singapore, it’s instantly clear how user experience suffers inside China.

As a general user experience measure, page load times are of huge importance to consider. Any international organization attempting to compete with internally-hosted Chinese services faces an instant impediment simply because of this.

The two main methods of tunneling through the GFW are:

- VPN

- SSH Tunnel (via Dynamic SOCKS5 proxy)

VPN subscriptions are trivial to buy into from a number of suppliers, especially when combined with the VPN comparison guide. Due to my technical background however, I roll my own using a combination of Puppet and OpenVPN. Other users are able to use a simple SOCKS5 proxy to pass all packets through a specified port to a remote machine. The following command will ensure that any application routing their packets through port 5000 will enter the tunnel and packets will continue to the destination at the remote host: ssh -D5000 [email protected]

Aside from VPNs, multinational corporations wishing to push content hosted outside China across the Great Firewall are able to take advantage of content delivery networks (CDNs) which maintain many local mirror servers globally to lower latency and speed up the delivery of content. Acquia customers have the option of utilizing Acquia Cloud Edge, a global CDN solution, uniquely tuned to Drupal with multiple points of presence inside China. By using internal mirrors for sites outside the GFW, the connection to these sites is massively sped up without having to procure additional infrastructure in potentially unsafe Chinese datacenters.

In summary, to me the GFW is an unfortunate addition to the internet. It threatens the open nature of how we communicate online. That being said, there are a multitude of ways that both individuals and organisations can evade these measures. These methods are inconvenient, but they do allow ideas to flow.