In this third installment of our series on conversational usability, we look at conversational design, an already well-explored area that is still burgeoning with emerging best practices.

Conversational design introduces complexity that can be challenging for even the most steeled organizations. Introduce the wildcard factor of voice assistants, and things become more difficult still. After all, in voice-driven interfaces, rather than designing on a visual or physical canvas, we need to conceive our creations on an aural and verbal canvas.

Effective conversational design comes not only from our understanding of natural conversation and human language, but also from the various ways in which researchers have attempted to distill often chaotic conversation into principles that can be applied to user interface design and human–computer interaction. In this post, we discuss some of the underpinnings of conversational design and dive into the two key aspects of design in conversational interfaces: the language itself, whether written or verbal; and the flows by which users navigate.

The aural and verbal canvas

One of the most crucial differences between web or graphic design and conversational design is the notion that while traditional designers focus primarily on visual and spatial elements in a physical space, conversational designers must reorient themselves to emphasize aural and verbal elements in either a physical space (for chatbots and other messaging bots) or an auditory environment (for voice assistants).

One way of envisioning how designers work in the conversational landscape is to inspect with a great deal of granularity the units with which they operate. For instance, print designers concern themselves with kerning, leading, and dots per inch, treating individual characters of text as the irreducible unit of their work. Web and graphic designers, meanwhile, traffic in the pixel and in the individual shape. In contrast, conversational designers must work first and foremost along the dimensions of the user's intent and the manifestations of that intent in the form of responses.

Ultimately, all conversational design boils down to how closely conversational interfaces can mimic or approximate the typical flow and expected language of a natural conversation. For machines, however, it can be difficult to handle all of the actions required to translate a particular intent (to order a pizza, for instance) into a request–response pattern that does not stymie the user's forward momentum. This means that we must conceive of ways to map out machine-driven trajectories for users that mirror the way they would expect authentic conversations to proceed.

Conversational maxims and key moments

One of the most compelling ways to facilitate a positive conversational user experience is by referring to previous scholarship on natural conversation. Conversational interfaces, after all, are unique insofar as they have a human and natural antecedent; common artificial interfaces like keyboards and mice are artificial, and their use is a learned behavior.

In her book Conversational Design, Erika Hall highlights philosopher H. Paul Grice's so-called conversational maxims, which enumerate what traits characterize the most effective conversations: quantity, quality, relation, manner, and a fifth added by Robin Lakoff, politeness. As we can see from these descriptions, Grice's conversational maxims are relevant to both transactional and informational conversations.

- Quantity. The ideal conversation tends to provide just the right amount of information to the conversants, not an excessive nor an insufficient amount.

- Quality. The ideal conversation displays truthfulness in that there are no falsehoods or information without evidence presented within that conversation.

- Relation. The ideal conversation does not veer from its original purpose; it remains relevant to the interlocutors' needs and hews to a topical track.

- Manner. The ideal conversation is unambiguous, brief, and orderly and involves just the right amount of dialogue to yield the desired outcome.

- Politeness. The ideal conversation is polite and without impositions, with empathetic consideration for the other person.

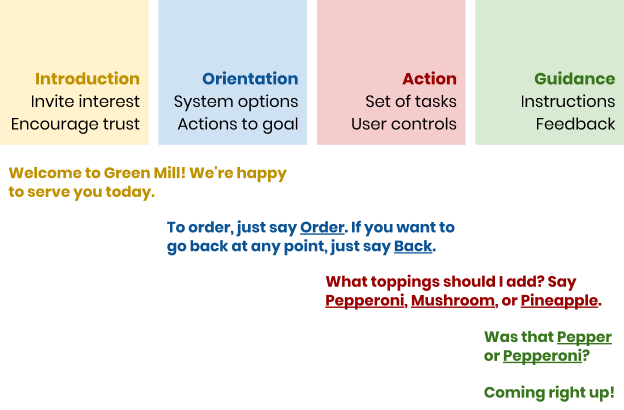

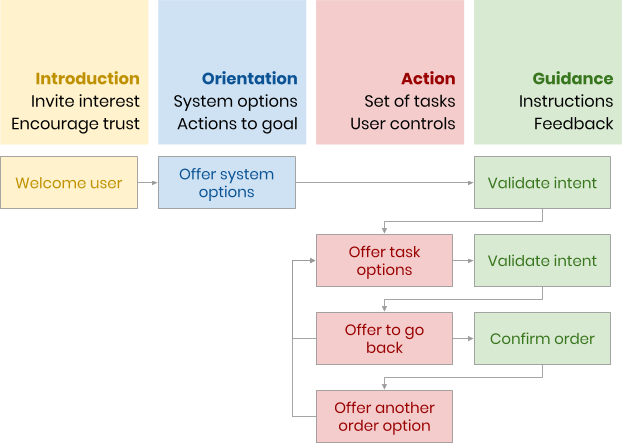

Based on Grice's conversational maxims, Hall outlines four key moments that characterize every optimal conversational interface but that also reflect the structure of a typical conversation in real life.

- Introduction. Invite interest and get the user excited about the conversation. Encourage trust and help the user feel at ease. This is the first impression they will have.

- Orientation. For users that are unfamiliar with conversational interfaces, an initial stage of orientation is important in order to provide system options and actions that can be undertaken in order to achieve a goal. This dovetails with information architecture.

- Action. At each stage in the conversation, the user should be presented with a set of options that represent tasks to move the conversation forward as well as user controls.

- Guidance. The interface should endeavor to provide clear and concise instructions when the user is expected to perform an action and feedback at the end of every interaction.

Coupled together, Grice's conversational maxims and Hall's key moments provide a foundation on which we can build compelling conversational interfaces. By mapping our conversational design to Hall's key moments and adhering to the principles outlined in Grice's conversational maxims, we can remain loyal to the spirit of natural conversation while offering our users another way to fulfill their needs or acquire information.

Designing language for conversational interfaces

Let's take a look at an example of how we can craft language that both represents a conversational interface well and sets up a positive experience for the user. Apart from translating intent into machine-driven action, one of the most intractable challenges facing conversational interfaces is to help the user feel confident even in the face of a conversation with a machine. The word choice and tone of your conversational interface can go a long ways to facilitating a positive interaction.

Consider the initial greeting, or introduction, that the Green Mill chatbot gives to the user.

Welcome to Green Mill! We're happy to serve you today.

Whether it is spoken or written, the sentence conveys a welcome and cultivates trust in the company from the user. A user interface should always strive to make the user feel some familiarity even in the face of an unfamiliar experience. In addition, the introduction also identifies the interface to the user, to distinguish it from other conversational interfaces. Note, however, that in the introduction there is no expectation for the user to respond to a question, though your interface may require an initial input from the user.

Next, during the orientation stage, the Green Mill chatbot offers key instructions to the user that indicate how to navigate the chatbot. This is particularly helpful if the user finds themselves at a place in the interface that they cannot escape. Offering system options that encompass the entire interface helps to put the user at ease.

To order, just say Order. If you want to go back at any point, just say Back. To start over, say Start over.

When the user proceeds past the global options and presents a response such as "Order," more localized options have to be given to the user in order for them to understand how to proceed to different states in the conversation. At this action stage, each interaction yields a unique set of options that direct the user in one direction or another. It is at this stage that how you design the flows across your information architecture (see next section) becomes crucial.

What toppings should I add? Say Pepperoni, Mushroom, or Pineapple.

What's clear from this example is that depending on where the user is in the interaction, the options will evolve. For instance, the interface may subsequently ask the user whether they would like to pay by cash or credit card.

Every action must have a corresponding reaction, and in the guidance stage, the Green Mill chatbot offers helpful feedback in response to the user's submissions as well as next steps to proceed. This guidance can take the form of requesting a clarification or more information or indicating to the user that their action has been understood by the interface. This allows us to distinguish feedback in response to a successful order from feedback in response to a failed one.

Consider this first response, which indicates the interface has not understood what the user said. In the following example, a voice assistant has trouble comprehending what the user has said, but on chatbots or other messaging bots, these responses could also result from typographical errors or spelling errors that obfuscate the true intent of the user.

Was that Pepper or Pepperoni?

And compare it to this second response, which indicates that the interface has interpreted the user's utterance and has translated the user's intent into an operation. In this instance, the interface reassures the user that their request is being processed, as it is unlikely that the user will receive any other direct feedback.

Coming right up!

As you can see, designing the right language for conversational interfaces requires best practices for writing that welcomes the user and puts them at ease. Scrutinize in particular the fact that even as the conversational interface proceeds in a methodical fashion, requesting clarification and ingesting user input, it still works hard to present a "human" face with more colloquial and informal turns of phrase like "We're happy to serve you today" and "Coming right up!"

Designing flows for conversational interfaces

Readers of this series will recall my coverage of conversational information architecture and the challenges in helping the user understand where they are within a user experience and in orienting them towards the navigational options that will lead them to the correct destination. Because conversational interfaces often require deep back-and-forth dialogues rather than a quick browse of a list of items like on a sitemap, they need a deliberate approach to help users understand where they are.

When it comes to a structure like the above, especially in voice assistants, the best way to assist the user in wayfinding is to provide consistency across each level of options. For instance, if the user has ordered a pizza and is now at payment, but she decides to add further toppings, each change in the user's location within the interface should be greeted with feedback and a repeated description of the options available at that node in the flow tree.

One of the most important traits of usability in general that bears considerable influence on conversational interfaces is the notion of discoverability. If your usability studies are showing that users are not reaching the lowermost portions of your flows, then you have a flow that travels too deeply and will never be found by most users. For this reason, I recommend that flows avoid excessive branching and instead focus on unidirectional, guided journeys that not only bring the user to the right location but also allow them to orient themselves within the interface.

As a conversational designer, you should endeavor to iterate on both the language you employ and the flows you delineate at each stage of your project's progress and particularly after receiving regular usability test results. You can draw out a flow like the above on a whiteboard and envision how each persona, under a different scenario, would travel through the interface, all the while keeping Hall's key moments at top of mind. You can also use such a flow diagram to pen the appropriate language for each interaction.

By focusing on these two elements of conversational design, your conversational interface will be not only robust and usable but also navigable and enjoyable to use.

Conclusion

Conversational design is a uniquely challenging area for exploration because it is so new and best practices are still emerging alongside the proliferation of devices and technologies that are scattered across the conversational landscape. In addition, the added complication of voice assistants demands that we consider not only visual and physical elements but also aural and verbal ones. In the end, nevertheless, the most important two components of any conversational design are the language that the interface traffics in and the flows by which users move about.

In the next installment of this series on building conversational interfaces, we turn our attention to content strategy. For many conversational interfaces, providing existing web content in a conversational setting is a challenging prerogative that requires considerable discovery and thinking. A well-informed and well-reasoned approach to content strategy can help any website with any content become a potential trove for effective conversational content. Last call; all aboard!